24th October, 2024

…sorry for the clickbait, this is not a joke. It’s another BCM post.

This post is going to be an update on my DA and the surrounding ethnographic research I’ve conducted in my chosen media niche. I have been looking at digital photography on Instagram and becoming more involved with the niche through my own photography account (@neeshphotography).

My investigation so far

I’ve made a few posts and stories so far, and come up with a caption template that I feel best addresses the research questions that I listed in my pitch. I’ve also been following other photography accounts, scrolling through hashtags and commenting/interacting with other photography accounts. I’ve been writing down my actions and observations using google keep, and even found some academic sources online which have helped me build on my understanding of this niche.

Obviously, I’ve spent a lot more time on Instagram than I’ve recorded so far, so it’s become a matter of tuning in consciously instead of mindlessly scrolling through my feed. Alas, I have identified three key epiphanies, which I’ll get into below.

Epiphany 1: You get what you give

When doing autoethnographic research, I need to investigate the personal experiences of users and observe how those experiences manifest themselves through their interaction with photography content. Logically, the best way to receive qualitative data through comments is to share personal experiences in the caption. This makes the photography work more accessible for discussion for someone who might otherwise feel intimidated or uninformed about photography jargon.

“On Instagram, people represent their social world and themselves, express their opinions, and practice social networking –all these, to some extent, are observable. Moreover, in tagging and captioning, users employ their own wording and thus provide access to vernacular categories”

Utekhin, Ilya. (2017). Small data first: pictures from Instagram as an ethnographic source. Russian Journal of Communication. 9. 1-16. 10.1080/19409419.2017.1327328.

I’ve been including personal anecdotes in the captions of my posts – details about the story behind the photo and thoughts on what I learned through that experience. It has encouraged users to respond in a more personal, detailed and thoughtful way, which is helpful from an ethnographic perspective.

Epiphany 2: Users see the photo, not the photography

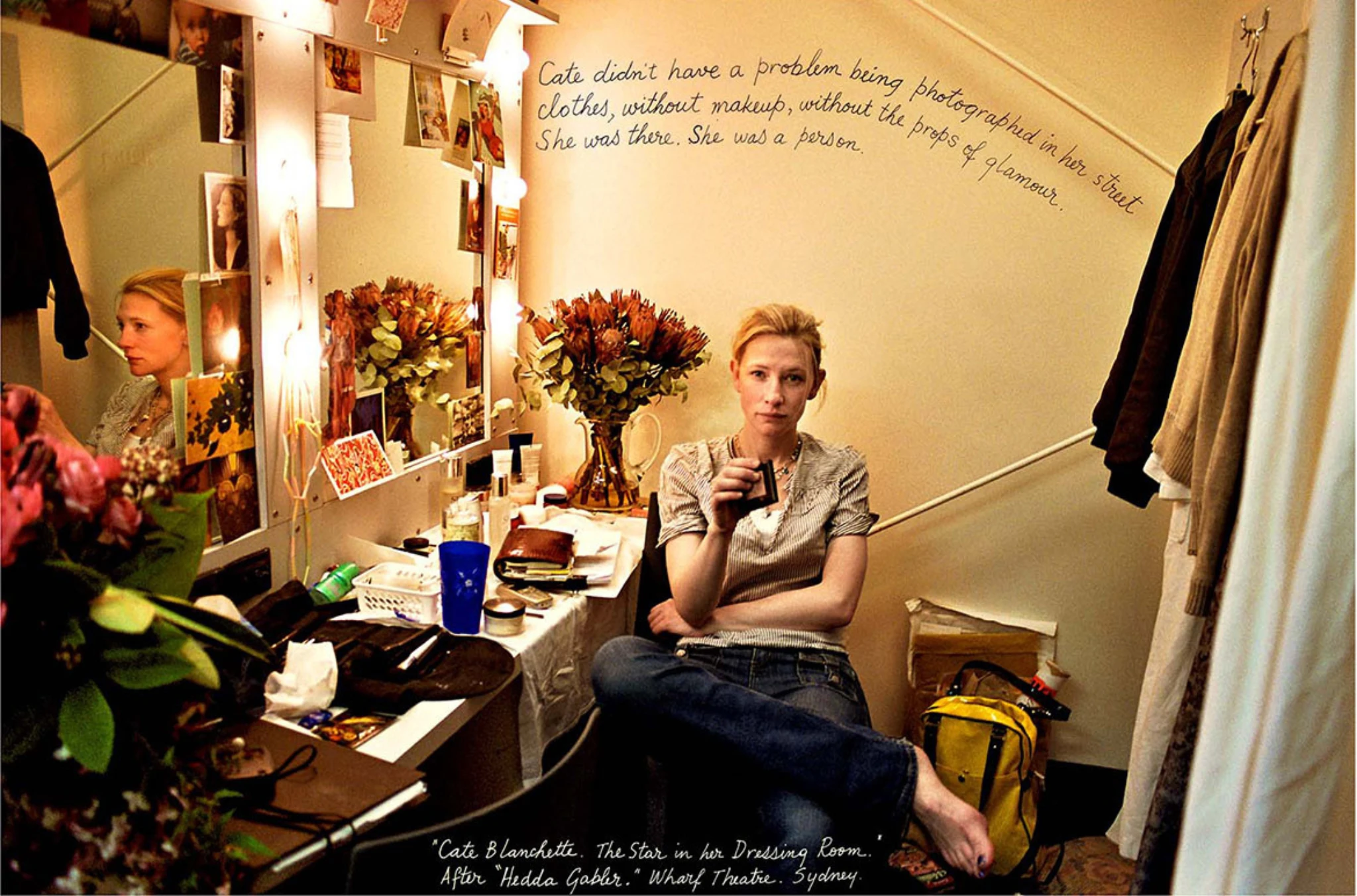

Instagram shows the final product of photography work, and much less often the process of creating images. It’s therefore understandable that photographers might struggle to convey a persona on Instagram. Especially in portrait work, when you’re the person behind the camera, the photo is not supposed to be about you. But of course, the style and creative decisions made by photographers are informed by their experiences and instincts. The users want to see themselves in your creative works, but unlike many other mediums, they’re unlikely to see you or consider your personal perspective.

“Research projects that employ big data and data visualization approach for analysis of users’ posts on Instagram deal with materials devoid of contextual information about the circumstances of taking photos and posting, but instead bear traces of users’ activities in the form of meta-data such as location, time and date.”

Utekhin, Ilya. (2017). Small data first: pictures from Instagram as an ethnographic source. Russian Journal of Communication. 9. 1-16. 10.1080/19409419.2017.1327328.

I encountered a set of 10 photos on my feed one day. The caption said, “1-10 choose your fav?” I scrolled through. These pictures were portraits of crying women Some of them were looking away, and some directly at the camera. I liked the ones where they were looking away, because they felt sadder, but the ones where they looked at the camera felt intimate in a different way. I described it in my notes as “breaking the fourth wall” because it was strange to realise consciously that a photographer was present.

At first, I thought that that intimacy must have been credited to the model’s expression. But on second thought, the photographer’s capturing, editing and posting definitely had more of an impact. I found it interesting then, that the caption did not go into detail about the thoughts of the photographer, but instead asked for my opinion.

While I’m scrolling through, I’ve tried to make sure that I’m consciously aware and thinking about what goes into making these posts for other creators, and how that process affects user interaction. I decided to include a ‘click-to-edit’ post on my story, but I might create some more ‘behind the scenes’ content, in order to overcome this block of perspective.

Epiphany 3: A picture paints a thousand words, but there’s no accounting for taste

Users often struggle to articulate the reason they are interested in an image. You are highly unlikely to receive detailed feedback on your images, past a “wow”-type comment, regardless of how impactful your image is. This is not particularly helpful in terms of ethnographic research.

I’ve started to become more thoughtful with my feedback when I comment under other photographer’s posts, attempting to detail what it is exactly that I like about the photo. This encourages more quality conversation and data to be observed. It might also help if I were to expressly ask for and encourage the opinion of my users.

The ‘lens’

For my final report, I feel that these epiphanies are easily applicable to a number of theories and frameworks which will allow me to look deeper into the research I’m conducting. For example, the idea of the invisibility of the photographer in the viewing of photographs is one that lends itself to the media effects model.