25th October, 2024

The other day, some friends and I wandered our way down to our local art gallery – a fun and free outing on a summer day woefully unfit for beach-going. The exhibition that the Wollongong Art Gallery is currently showing is ‘Thinking Through Pink’ – Curated by Sally Gray, and it got me thinking.

As we giggled and gawked our way through the gallery, taking in the various shades and tones of pink, it became obvious and interesting how this color has been both embraced and rejected in art and society. While it has often been considered a symbol of femininity and innocence, it has also been used to challenge these notions and present a more nuanced, complex view of gender and identity. The exhibition shows how pink can be both playful and powerful, and how it continues to evolve, shaping and reflecting our cultural values throughout history.

I often think, write and talk about my (at times) complicated relationship to my feminity. Growing up, I was the ‘pink sister’ – you know, when Christmas presents were handed around, I was given the pink version, and they gave my sister the purple. I don’t remember ever choosing that for myself, but I definitely embraced it as a child. The ‘pink princess’ identity is bold, sweet, prissy, sensitive, pretty… all that makes little boys cry “pink is a girl colour!”

“Pink is not the opposite of black, they’re actually rather similar in terms of cultural capital, being used to advance protest and speak out on adversity.”

We’ve all, at some stage, heard a woman express their utter disgust with the colour pink. “I hate pink,” they say, judgement flashing across their face. Ask them why, and they rarely had an answer. For most, it was good old internalised misogyny. To have such a visceral reaction to a colour that is viewed to represent all it means to be feminine is to indicate that all of those “feminine” traits it reflects are undesirable. I’ve never heard a woman exclaim, “I can’t wear blue, that’s a boy colour!”. I’ve heard no one say that they hate blue, in fact.

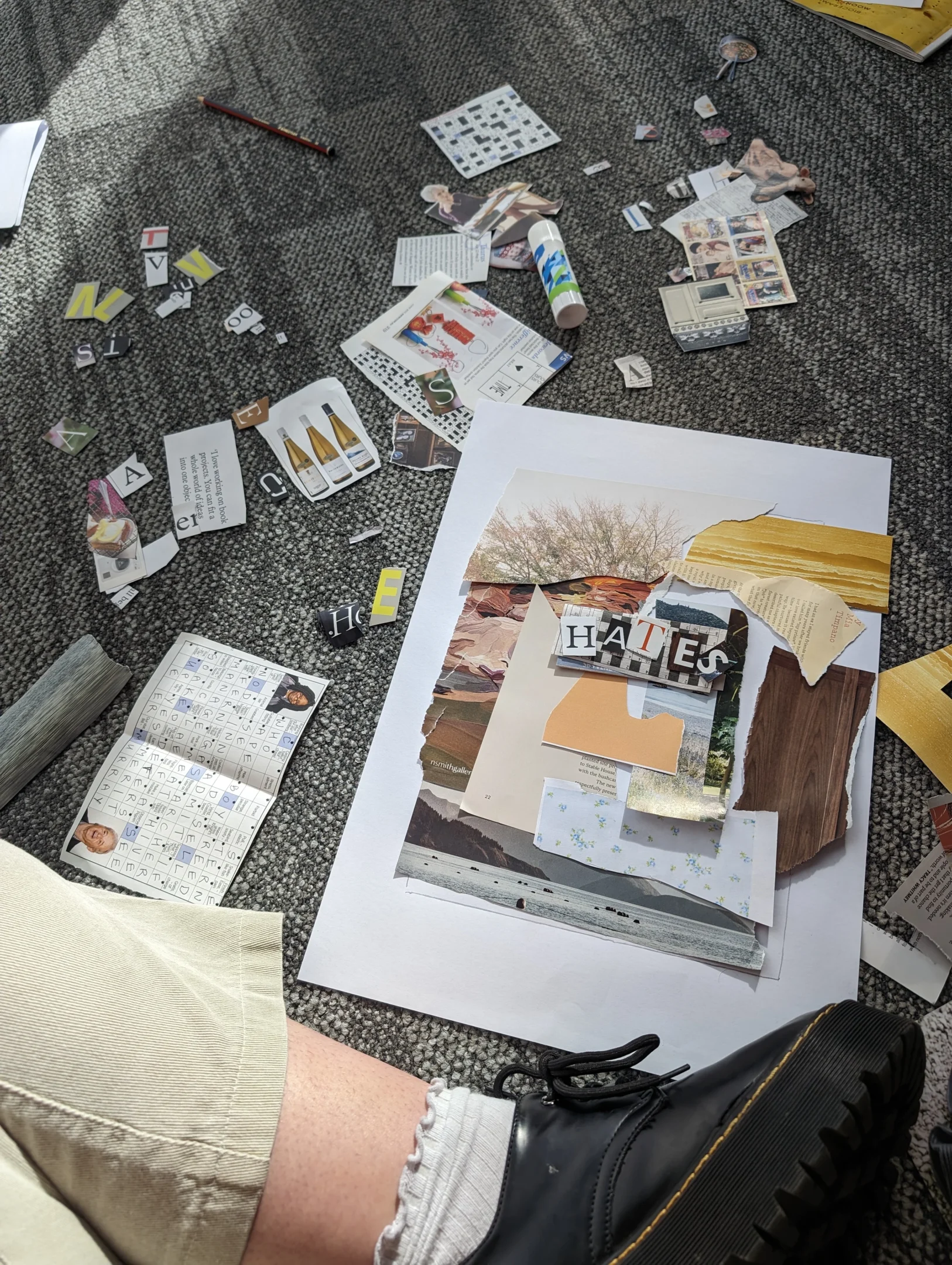

At some stage, I definitely relinquished my affinity for the colour. For most of my adolescence, I opted for maroon and navies. We were all trying desperately hard to assert how we “weren’t like other girls” in 2016’s Tumblr era, as if it would get us a shot at dating a member of 5SOS. I’d probably have said I hated pink at that point, but I didn’t. I was uncomfortable with it because it represented an identity that someone else chose on my behalf, and because of course I’d had it in my head that it was a bad thing to be prissy, and sensitive, and feminine. I’ve since deconstructed the pathway in my head that links femininity to weakness and weakness to danger. You can read about it here if you like, so I won’t get into it.

Nowadays, I find young people are more likely to wear pink items. One of the major cultural impacts of the pandemic and the rise of TikTok was the tentative death of cringe culture. Gen Z’s affinity for shameless authenticity stripped the online culture of its millennial roots in curated homogeneity, and one way we observe this change is through pink. It’s almost viewed as a political statement to align yourself with the colour. Think of the ‘Bimboficiation’ movement – at this stage in history, women are in the process of reclaiming feminine attributes and stereotypes that were thought of poorly 5, 10 and 20 years ago.

Taylorlani is one of my best friends, and we’ve often spoken about concepts for portraits I might take of her. Their grungy, emo, all-black aesthetic is seemingly at odds with her pronounced love of pink. The first time we met, I thought “it would be so funny and beautiful to put you in the middle of a field of sunflowers”. Think Wednesday Addams in a sparkly pink jumping castle. But it makes sense. Pink often indicates a point of contrast where none should necessarily exist. Pink is not the opposite of black, they’re actually rather similar in terms of cultural capital, being used to advance protest and speak out on adversity.

“The ‘pink princess’ identity is bold, sweet, prissy, sensitive, pretty… all that makes little boys cry “pink is a girl colour!””

Pink has long been utilised as a point of protest for women and queer people. From Barbie dolls to pussy hats at the women’s marches, it has had a significance in everyone’s lives, the shaping of our identities and our relationship to that identity.

Pink has been a mark of luxury for a very long time. From Jackie Kennedy to Paris Hilton, there is an aspect of class and eloquence associated with the lighter shades. Although certain shades have been thought of as tacky and cheap. Pink is such a rich colour, if not only because each shade implies another set of political disposition.

Red is another colour that is widely antagonising – it represents passion, anger, sexuality, boldness and danger. There’s something to be said for pink as a watered-down red and how our treatment of both colours has reinforced archetypes of feminity – the Madonna-Whore complex and so on. If you take into account that red is just dark pink, it becomes really obvious that pink was at some stage hand selected from the colour wheel to represent a set of ideas in a way that blue, green or yellow aren’t.

Pink is a more divisive colour than most, simply because it represents ideas about identity and gender and carries the weight of its political implications. It is redefined and reimagined, individually and societally, over and over as attitudes toward identity and femininity grow and change. If I were to time travel 50 years in the future, the first thing I’d do is ask the nearest person if they like pink.